The Psychology of Response

Overview

How people process and respond to marketing research questions—biases, heuristics, and cognitive response patterns.

Larry Vincent,

Professor of the Practice

of Marketing

MKT 512

January 22, 2026

Biases and

heuristics

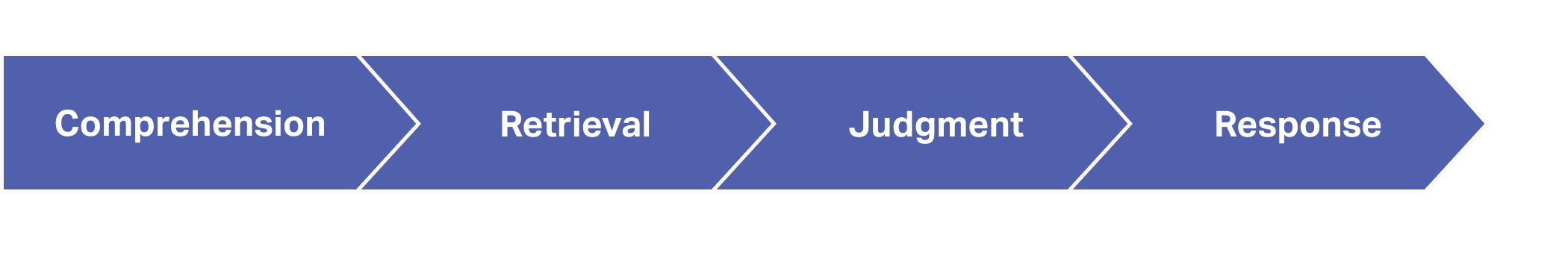

The psychology of response

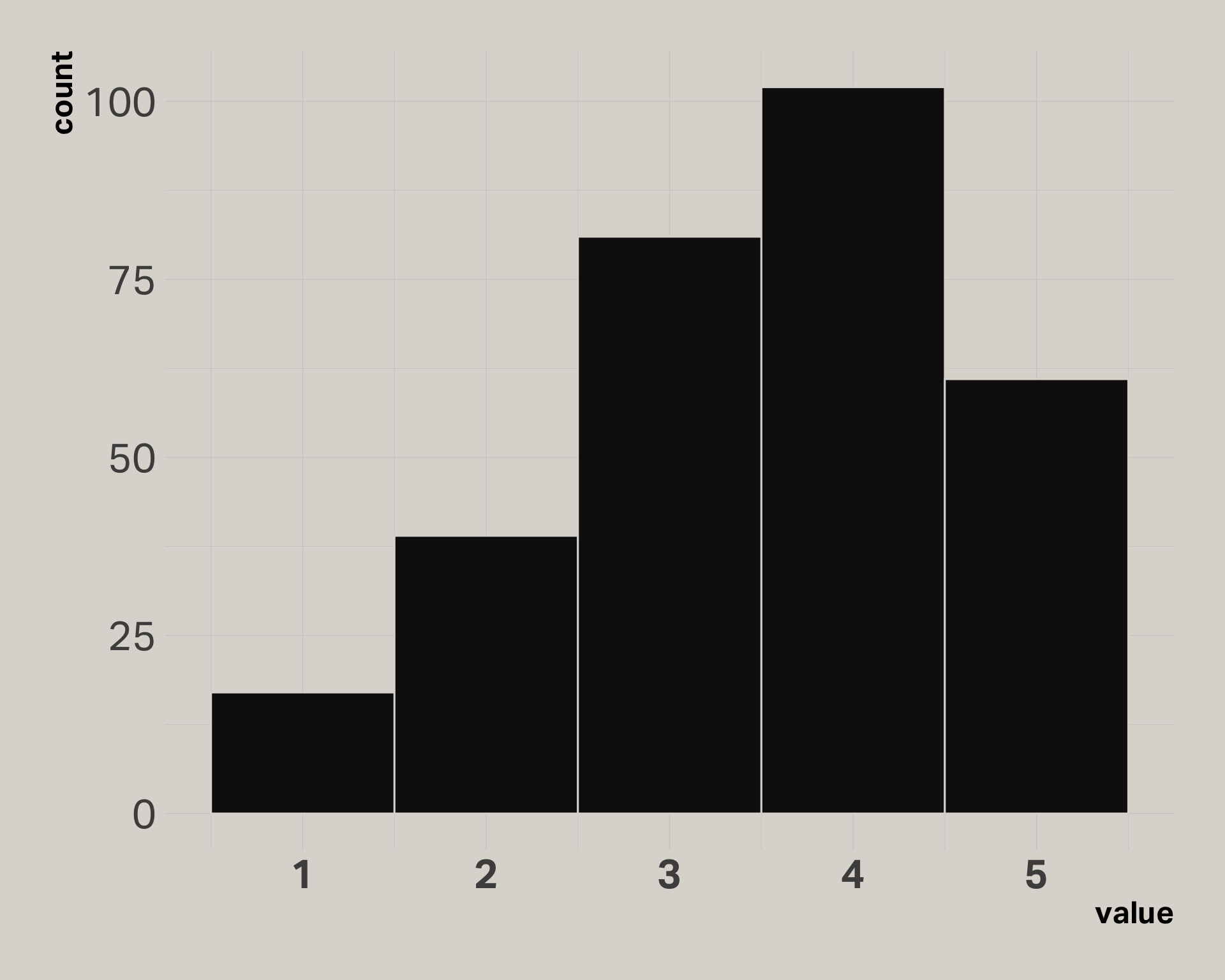

Stage 1

Comprehension

- Definition:

Understanding what the question is asking - Where it goes wrong:

Ambiguously phrased questions, unfamiliar terms,

complex syntax - Tips:

Craft clear, concise questions; test your

questions rigorously

Stage 2

Retrieval

- Definition:

Recalling relevant information from memory - Where it goes wrong:

Memory errors, recall biases (recency, primacy, etc.) - Tips:

Use specific time frames or cues to aid recall; consider exhibits and tangible timelines to help respondents walk through their experience

Stage 3

Judgment

- Definition:

Evaluating and synthesizing retrieved information - Where it goes wrong:

Heuristics and biases; social desirability; threatening questions - Tips:

Be aware of how phrasing or question order might influence judgment

Stage 4

Response

- Definition:

Mapping the judgment onto the response options provided or within the respondent’s available vocabulary - Where it goes wrong:

Limited response options, scale issues, lexicon - Tips:

Provide a comfortable environment, encourage elaboration, and watch for non-verbal cues

Analyze These Questions

- Are you a responsible consumer who always chooses environmentally friendly products?

- How many times did you visit fast-food restaurants in the past year?

- To what extent do you believe that the current macroeconomic factors are influencing consumer discretionary spending patterns in your household?

- On a scale from 1 to 100, how satisfied are you with your current smartphone?

Heuristics

Why heuristics matter

- Subconsciously influence how respondents answer questions

- Provides context and shortcuts that can improve how you craft questions

- Helps researcher to look beyond initial responses and probe for deeper insight

Common heuristics

Availability

- Relying on immediate examples when evaluating something.

- Can lead to: Overestimating importance of recent or memorable events.

Representativeness

- Assessing similarity of objects and organizing based on category prototype.

- Can lead to: Stereotyping or ignoring base rates.

Anchoring

- Relying heavily on first piece of information encountered.

- Can lead to: Biased decision-making, especially in estimations.

Write down as many brands as you can think of that are associated with artificial intelligence.

Availability heuristic

Don’t start with the obvious–Avoid leading with high-profile examples (e.g., ChatGPT, Tesla) before participants respond.

Broaden the frame–Ask open questions that invite multiple categories (e.g., “What brands, companies, or technologies come to mind when you think of AI?”).

Encourage recall beyond the recent-–Prompt with timeframes (“thinking back over the last 10 years…”) to reduce recency effects.

Rotate prompts-– If showing stimuli (logos, ads, concepts), vary the order across groups.

Probe for the less familiar–-Follow up with: “Are there any others that may not be as widely known?”

Be mindful of silence–-Resist filling gaps with your own examples; let participants stretch their memory.

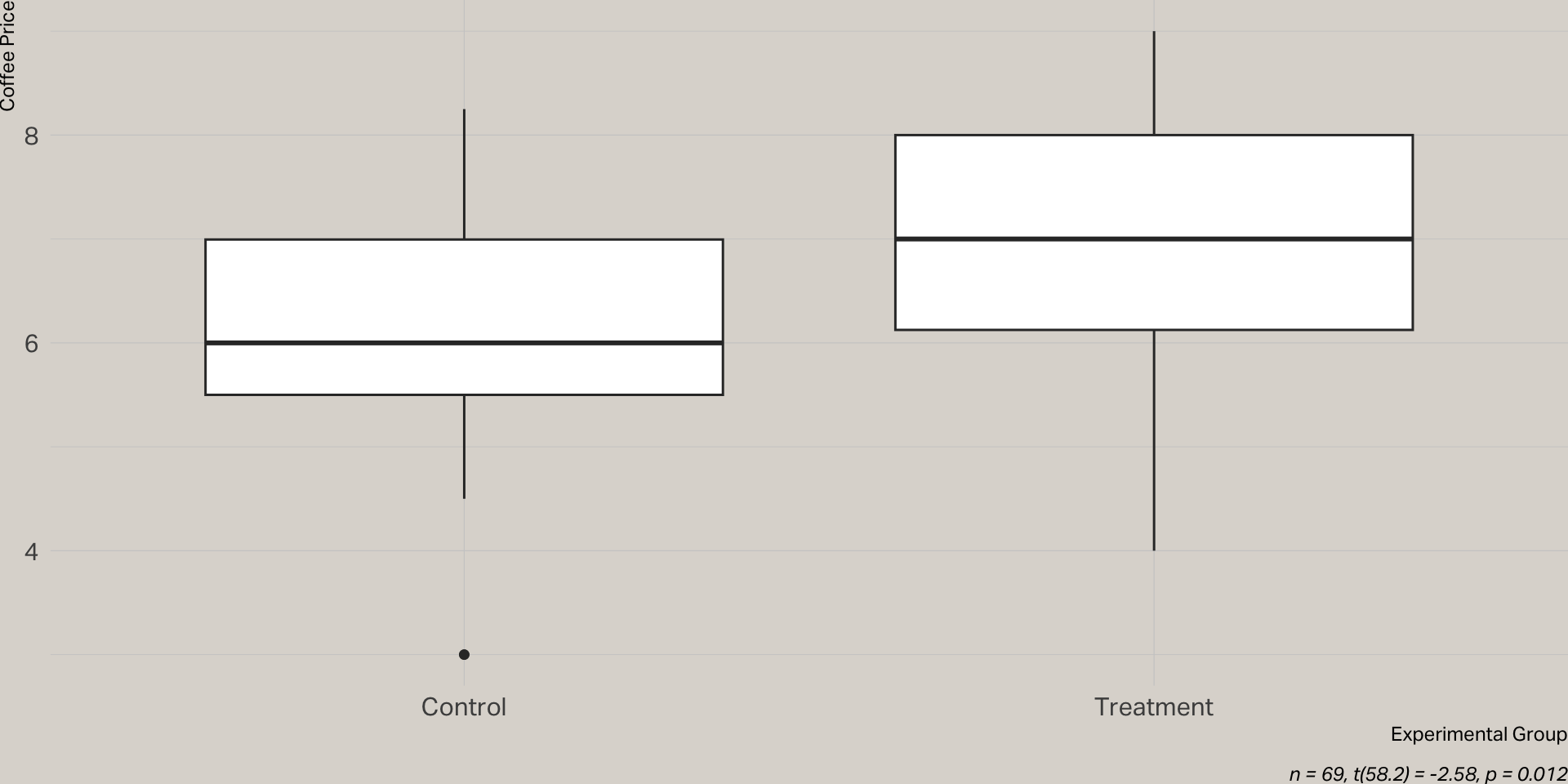

Anchoring

To demonstrate anchoring, consider a question I posed to a previous group of students in a weekend poll.

Control Group

Q: What do you think is a reasonable price for a large specialty coffee drink at an independent coffee shop near campus?

Treatment Group

Q: The most expensive coffee drink at the campus Starbucks costs $8.50. Now, thinking about coffee pricing in general, what do you think is a reasonable price for a large specialty coffee drink at an independent coffee shop near campus?

Anchoring

Moderating anchoring

Avoid giving participants a starting number unless it’s deliberate.

Rotate order of numeric questions when possible.

Use open-ended before closed-ended (“What feels reasonable?” before “Would you pay $X?”).

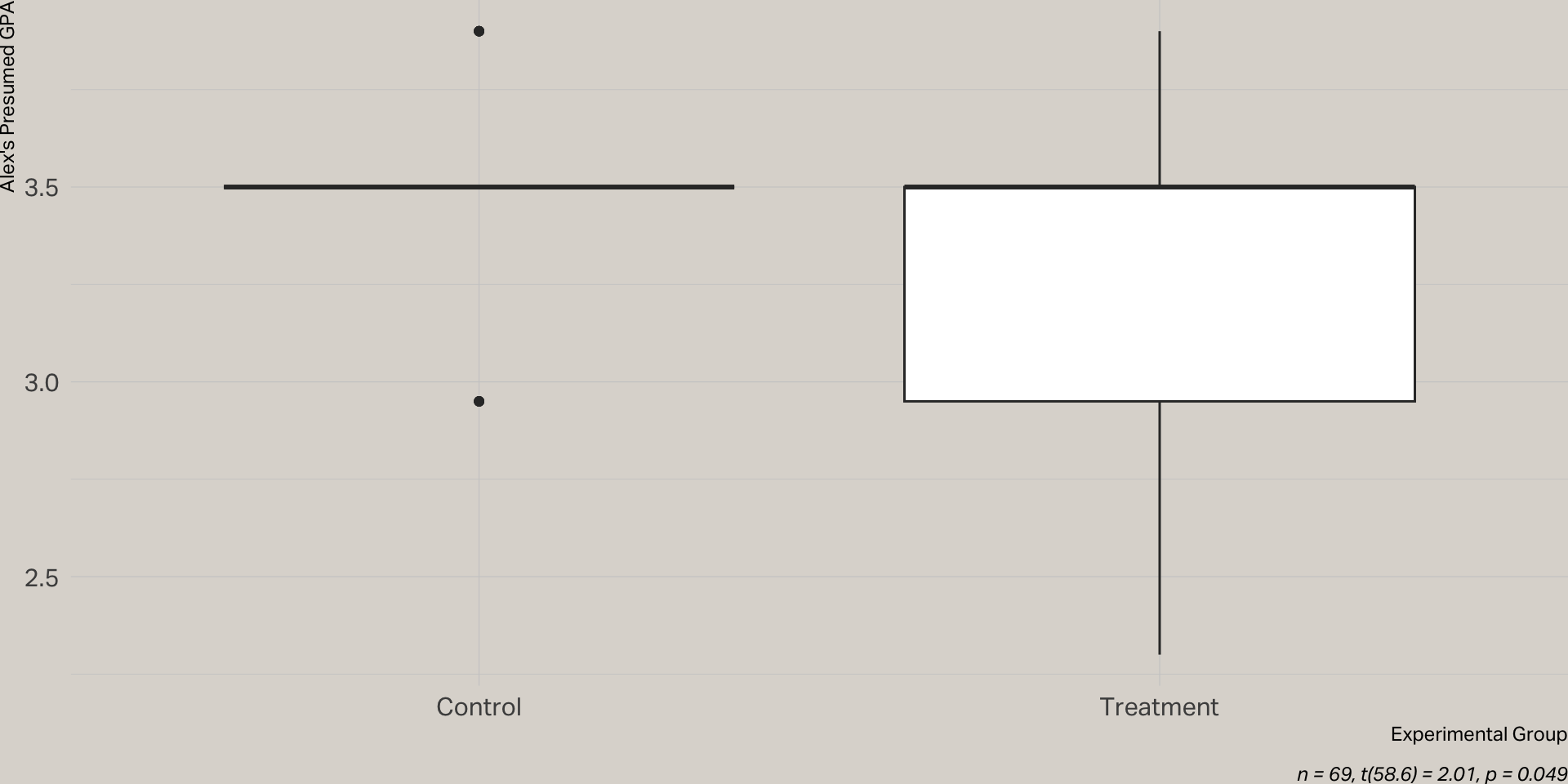

Representativeness

Another question I asked in a student poll.

Control Group

Q: Meet Alex: They are an undegraduate student here at USC. What do you think Alex’s GPA is most likely to be?

Treatment Group

Q: Meet Alex: They are an undegraduate student here at USC. They spend 6+ hours daily playing video games, often stay up until 3 AM gaming, have gaming posters all over their dorm room, and can discuss the latest game releases for hours. Alex is known around his residential college as ‘the gamer.’ What do you think Alex’s GPA is most likely to be?

Representativeness

Moderating representativeness

Be careful describing participants or stimuli with traits that might trigger stereotypes.

Probe for exceptions (“Do all people like this fit that description?”).

Remind yourself to check against actual data, not perceived type.

Other heuristics, biases and considerations

What are threatening questions?

- Questions about socially desirable or undesirable behavior

- Questions dealing with financial or health status

- Questions about sex, politics, religion, or any other topic that an average respondent might hesitate to discuss with a stranger

Confirmation bias

Tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions.

How often do you buy organic produce to support environmental sustainability?

How often do you buy organic produce to support environmental sustainability?

Social Desirability Bias

What about this question?

How much do you agree or disagree with the statements below?

- Our new product is user-friendly.

- Our new product is innovative.

1 = Strongly disagree

2 = Disagree

3 = Neither agree nor disagree

4 = Agree

5 = Strongly agree

Acquiescence bias

How much do you agree or disagree with the statements below?

- Our new product is user-friendly.

- Our new product is innovative.

1 = Strongly disagree

2 = Disagree

3 = Neither agree nor disagree

4 = Agree

5 = Strongly agree

How it manifests in qualitative research?

Examples:

- Leading questions: “You probably found that feature helpful, right?”

- Seeking confirmation: “So you like the new design?”

- Interview dynamic: Participants want to be “good respondents” and avoid conflict

Better approaches:

- “Tell me about your experience with that feature.”

- “What’s your reaction to this design?”

Question Design Issues

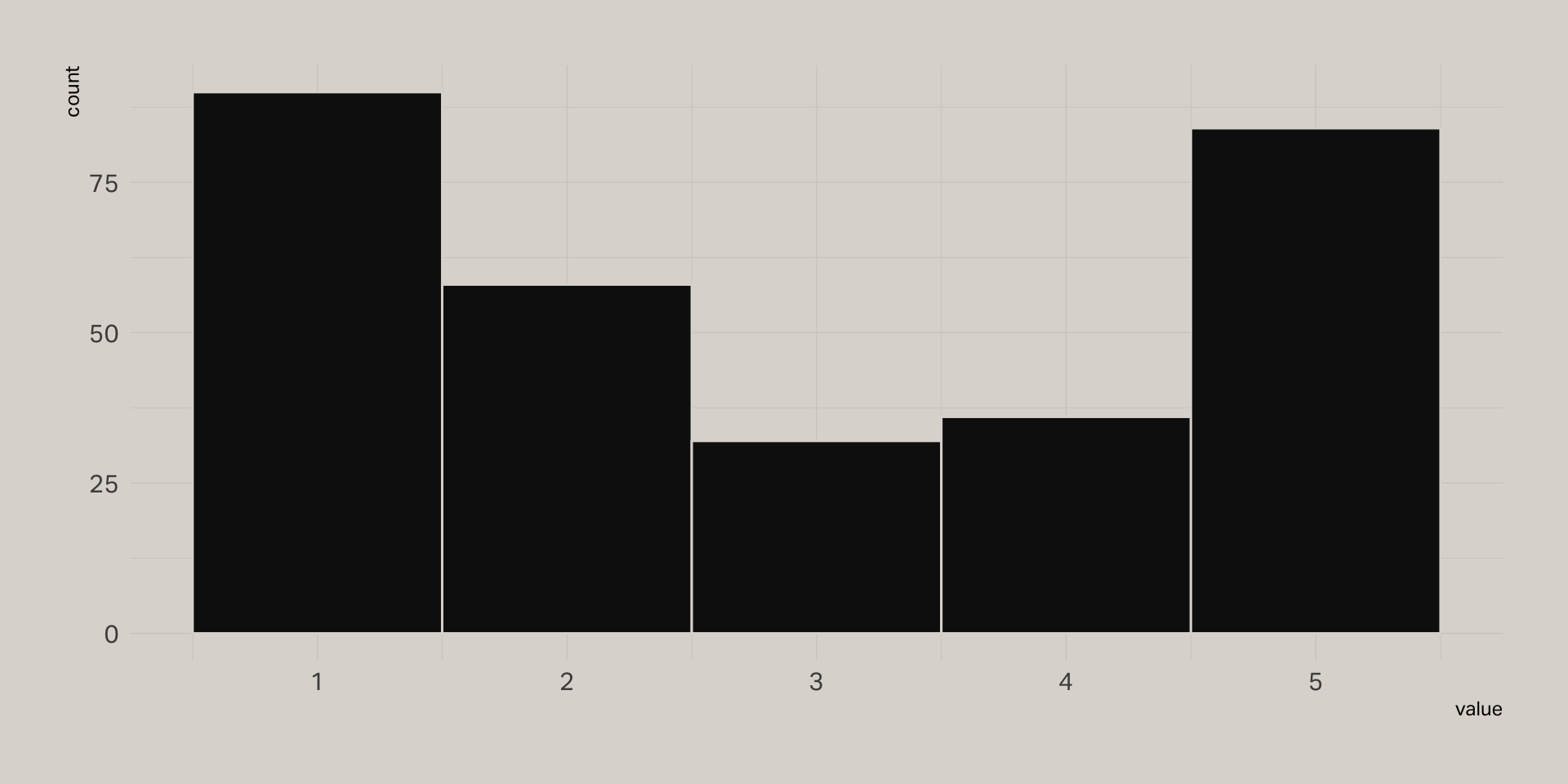

Evaluate this question:

Primacy and recency effects

Mitigating

General rules of thumb:

- First and last items in any list get disproportionate attention

- Middle items are most likely to be overlooked or forgotten

- Effect is stronger when participants are rushed or cognitively overloaded

- Written lists show stronger primacy effects; spoken lists show stronger recency effects

In qualitative research:

- Rotate order of concepts, stimuli, or topics across interviews

- Don’t always start with your “favorite” concept or most important question

- Be aware that early themes discussed may influence how participants frame later topics

- Consider breaking up long lists of probes or topics with natural conversation

- Save your most important questions for the middle of the session when rapport is built but fatigue hasn’t set in

Beware your framing!

How likely are you to purchase our new yogurt, which is 95% fat-free?

vs.

How likely are you to purchase our new yogurt, which contains only 5% milk fat?

Study Design Issues

Passionate about gourmet coffee? Take our survey for a chance to win a year’s supply!

Passionate about gourmet coffee? Take our survey for a chance to win a year’s supply!

Self-Selection Bias

Non-response bias

Non-Response bias

The impact from the lack of response by significant groups in your sample who have material representation in the population of your study.

Present in almost every study.

Affect heuristic

Social Pressure Biases