Qualitative Research

Overview

Introduction to qualitative field work, heuristics, and the psychology of response.

Larry Vincent,

Professor of the Practice

of Marketing

MKT 512

September 16, 2025

Up Next…

Hanna Stein

- Veteran mix-methods market researcher

- Senior roles at Meta, Twitter, Mattel, and Hasbro

- Frequent and popular guest speaker for this course

- Be on time and bring your questions!

Qualitative Kick-Off Briefings

IA1

Assignment:

Conduct a 1:1 customer interview to understand the relationship dynamics between the customer and the brand.

Method:

Determine context in IA1 brief based on last digit in your USC ID. Then, structure an interview guide, recruit a respondent, and interview them according to the contextual criteria.

Report:

Detail findings in a slide presentation. Be sure to use evidence from fieldwork to support your insights.

Tips:

Get out of comfort zone. Use techniques covered in this module, such as projective techniques.

Due Date: October 2, 2025 at start of the class.

Group Project: Qualitative

Purpose:

Exploratory start to your research question–defines and refines the parameters of your experiment.

Requirements:

- Recruit 10 customers of the brand

- Either do 10 IDIs or 1-2 focus groups (optimal focus group size = 6-8)

- Sessions should be about 45 minutes to an hour for IDIs and about 60-90 minutes for a focus group

Deliverable:

- 10-15 annotated slides

- Be sure to include evidence to support your insights

- Assume the deliverable is being read by a senior decision-maker at your company (don’t tell them what they already would know)

Now is a good time to have “the talk.”

Fieldwork and Ethics

- Global standard for ethical research (by ICC & ESOMAR).

- Protects participants, ensures honesty & fairness.

- Builds trust in research and credibility for researchers.

- Practicing it now = good professional habits for later.

Why ethics matters…

- Research relies on trust—from participants, clients, and the public.

- One bad practice can harm individuals and damage the credibility of the entire field.

- If we don’t protect it, primary research becomes noisier, costlier, and less credible.

Five Core Principles

- Be honest and transparent.

Don’t mislead participants about what you’re doing. - Do no harm.

Respect people’s dignity and wellbeing. - Protect privacy.

Handle personal data carefully; safeguard identities. - Build trust.

Don’t do anything that causes doubt about research practice. - Take responsibility.

Whether you’re a lead researcher or part of a team, own your role in ethical practice.

Your responsibility to participants

- Respect voluntary participation–people can say no, or stop at any time.

- Generate informed consent–make sure participants understand what they’re agreeing to.

- Take special care with vulnerable groups–children, young people, or those with limited ability to consent require extra safeguards.

- Create a safe space for privacy–collect only the information that is necessary (“data minimization”), and protect it. Never use it for other purposes.

When in doubt…

Am I being transparent, respectful, and careful with data?

Am I treating research participants like I’d treat friend or a loved one if they were one of my respondents.

Am I acting in a manner that will ensure lasting trust for the practice of research.

USC Code of Research Conduct

All of the above, plus …

Accountability

Own your work. If you hit a snag, explain it rather than covering it up.Fairness & Credit

Share work equitably in your team. Give proper credit to classmates and sources.Data Stewardship

Keep data safe, and if you use your project later (e.g., for job interviews), make sure you protect confidentiality or sensitive information.

Final note on ethics

Your capstone project is built around running an experiment. Remember: good science doesn’t always confirm your hunch. If your results support the null hypothesis, that’s still valuable. What matters for your grade is the quality of your design, your execution, and the interpretation of the work. You are not being graded on whether or not your hypothesis turns out to be ‘right.’ You are being graded on your capacity to create useful, ethical, and reproducible research.

Intro to

Qualitative

Qualitative research

The systematic study of people’s experiences, meanings, and behaviors through in-depth, non-numerical methods like interviews, observation, and text analysis.

Purpose

- Explains why/how, not how much

- Surfaces language, mental models, jobs-to-be-done, tensions, journeys

What’s the difference?

Quantitative

- Categories defined before study

- Narrow field of vision

- Force respondents to respond readily and unambiguously

- Requires statistically significant sample

- More focused on techniques (i.e. statistical approaches)

Qualitative

- Categories are defined during study

- Broader range and less precise vision

- Allows respondents to elaborate; use own language

- Allows smaller samples

- Focused on collective wisdom and interpretation

Source: Grant McCracken; The Long Interview

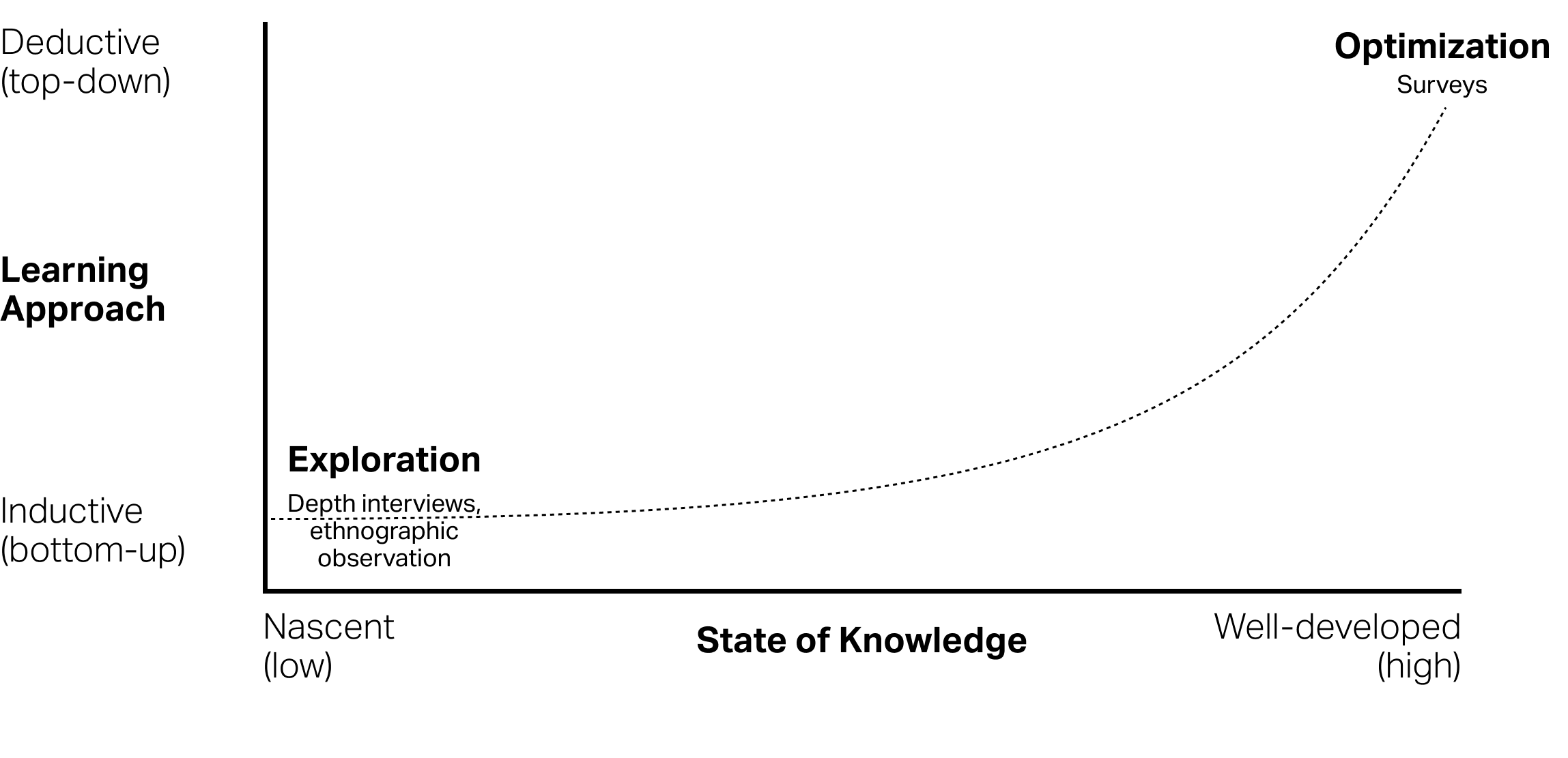

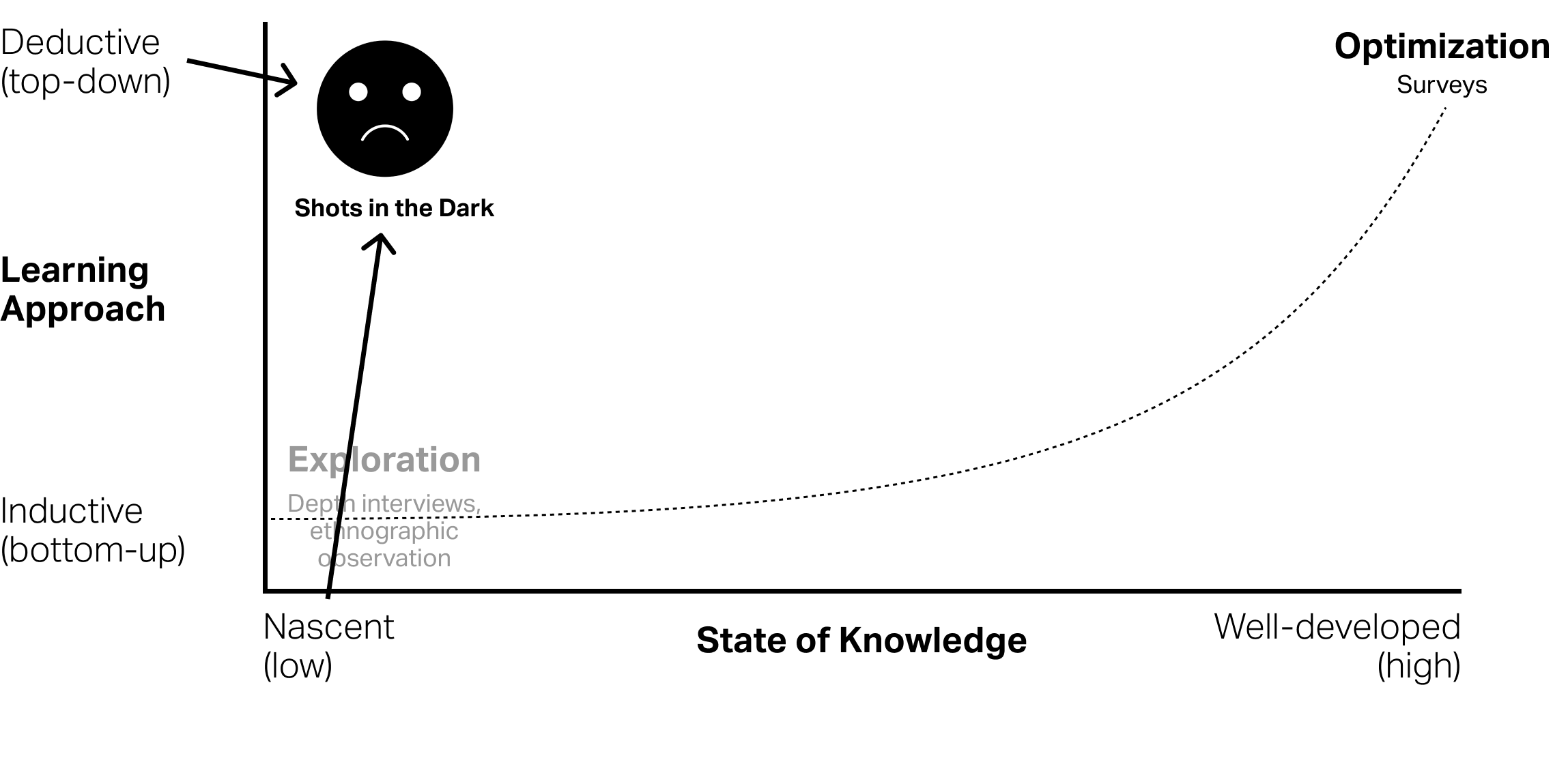

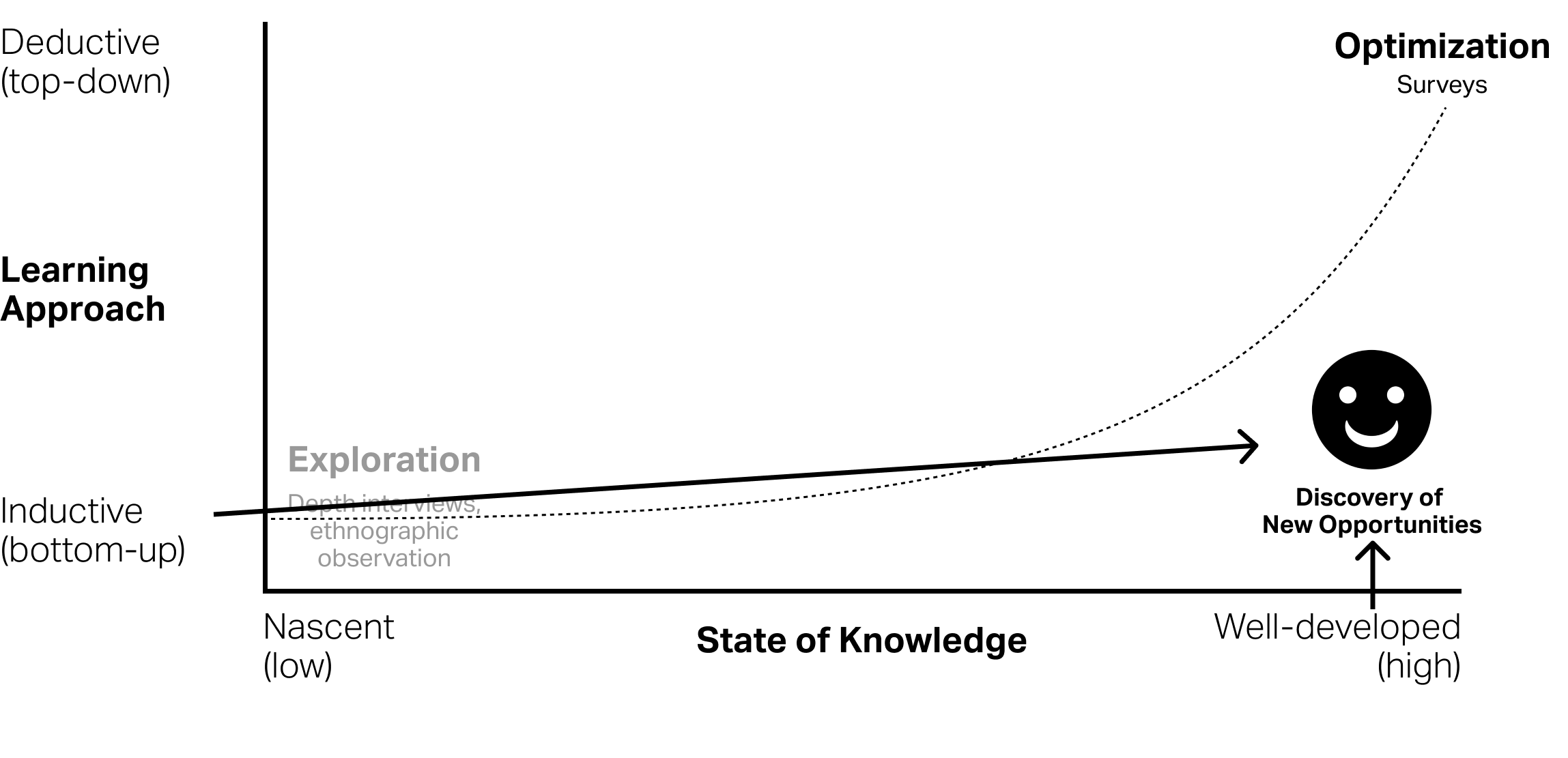

Deductive vs. Inductive

Deductive vs. Inductive

Deductive vs. Inductive

Qualitative modes

- Exploratory–define problems in more detail; suggest hypotheses to be tested in later research; generate concepts; get preliminary reactions to concepts; pretest structured questionnaires

- Orientation–learn consumer’s vantage point and vocabulary; gain insight into an environment that is unfamiliar to the researcher (or research sponsor)

- Clinical–gain insight into specific topics that are hard or impossible to pursue with surveys or more structured approaches

Biases and

heuristics

The psychology of response

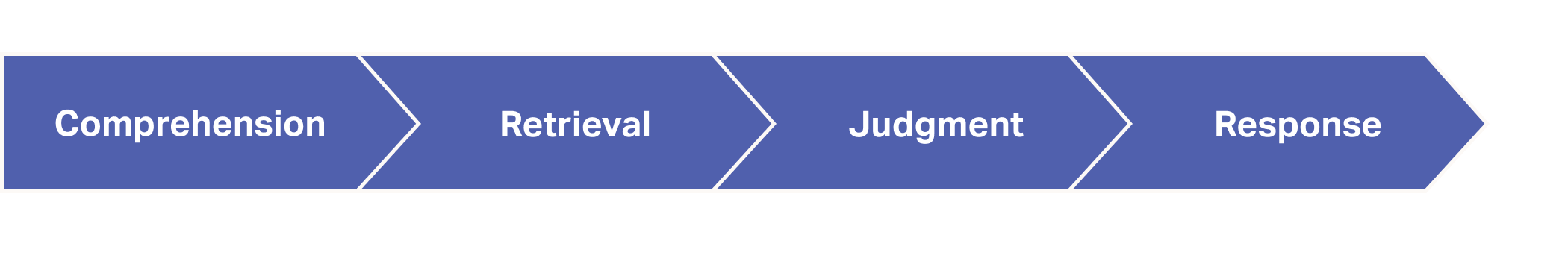

Stage 1

Comprehension

- Definition:

Understanding what the question is asking - Where it goes wrong:

Ambiguously phrased questions, unfamiliar terms,

complex syntax - Tips:

Craft clear, concise questions; test your

questions rigorously

To what extent do you believe that the current macroeconomic factors are influencing consumer discretionary spending patterns in your household?”

Stage 2

Retrieval

- Definition:

Recalling relevant information from memory - Where it goes wrong:

Memory errors, recall biases (recency, primacy, etc.) - Tips:

Use specific time frames or cues to aid recall; consider exhibits and tangible timelines to help respondents walk through their experience

How many times did you visit fast-food restaurants in the past year?

Stage 3

Judgment

- Definition:

Evaluating and synthesizing retrieved information - Where it goes wrong:

Heuristics and biases; social desirability; threatening questions - Tips:

Be aware of how phrasing or question order might influence judgment

Are you a responsible consumer who always chooses environmentally friendly products?

Stage 4

Response

- Definition:

Mapping the judgment onto the response options provided or within the respondent’s available vocabulary - Where it goes wrong:

Limited response options, scale issues, lexicon - Tips:

Provide a comfortable environment, encourage elaboration, and watch for non-verbal cues

On a scale from 1 to 100, how satisfied are you with your current smartphone?

Heuristics

Why heuristics matter

- Subconsciously influence how respondents answer questions

- Provides context and shortcuts that can improve how you craft questions

- Helps researcher to look beyond initial responses and probe for deeper insight

Common heuristics

Availability

- Relying on immediate examples when evaluating something.

- Can lead to: Overestimating importance of recent or memorable events.

Representativeness

- Assessing similarity of objects and organizing based on category prototype.

- Can lead to: Stereotyping or ignoring base rates.

Anchoring

- Relying heavily on first piece of information encountered.

- Can lead to: Biased decision-making, especially in estimations.

Write down as many brands as you can think of that are associated with artificial intelligence.

Availability heuristic

Don’t start with the obvious–Avoid leading with high-profile examples (e.g., ChatGPT, Tesla) before participants respond.

Broaden the frame–Ask open questions that invite multiple categories (e.g., “What brands, companies, or technologies come to mind when you think of AI?”).

Encourage recall beyond the recent-–Prompt with timeframes (“thinking back over the last 10 years…”) to reduce recency effects.

Rotate prompts-– If showing stimuli (logos, ads, concepts), vary the order across groups.

Probe for the less familiar–-Follow up with: “Are there any others that may not be as widely known?”

Be mindful of silence–-Resist filling gaps with your own examples; let participants stretch their memory.

Anchoring

To demonstrate anchoring, consider one of the questions I posed to you in the weekend poll.

Control Group

Q: What do you think is a reasonable price for a large specialty coffee drink at an independent coffee shop near campus?

Treatment Group

Q: The most expensive coffee drink at the campus Starbucks costs $8.50. Now, thinking about coffee pricing in general, what do you think is a reasonable price for a large specialty coffee drink at an independent coffee shop near campus?

Anchoring

Moderating anchoring

Avoid giving participants a starting number unless it’s deliberate.

Rotate order of numeric questions when possible.

Use open-ended before closed-ended (“What feels reasonable?” before “Would you pay $X?”).

Representativeness

Another question I posed to you in the weekend poll.

Control Group

Q: Meet Alex: They are an undegraduate student here at USC. What do you think Alex’s GPA is most likely to be?

Treatment Group

Q: Meet Alex: They are an undegraduate student here at USC. They spend 6+ hours daily playing video games, often stay up until 3 AM gaming, have gaming posters all over their dorm room, and can discuss the latest game releases for hours. Alex is known around his residential college as ‘the gamer.’ What do you think Alex’s GPA is most likely to be?

Representativeness

Moderating representativeness

Be careful describing participants or stimuli with traits that might trigger stereotypes.

Probe for exceptions (“Do all people like this fit that description?”).

Remind yourself to check against actual data, not perceived type.

Other heuristics, biases and considerations

What are threatening questions?

- Questions about socially desirable or undesirable behavior

- Questions dealing with financial or health status

- Questions about sex, politics, religion, or any other topic that an average respondent might hesitate to discuss with a stranger

Confirmation bias

Tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions

How often do you buy organic produce to support environmental sustainability?

How often do you buy organic produce to support environmental sustainability?

Social Desirability Bias

What about this question?

How much do you agree or disagree with the statements below?

- Our new product is user-friendly.

- Our new product is innovative.

1 = Strongly agree

2 = Agree

3 = Neither agree nor disagree

4 = Disagree

5 = Strongly disagree

Acquiescence bias

How much do you agree or disagree with the statements below?

- Our new product is user-friendly.

- Our new product is innovative.

1 = Strongly agree

2 = Agree

3 = Neither agree nor disagree

4 = Disagree

5 = Strongly disagree

How it manifests in qualitative research?

Examples:

- Leading questions: “You probably found that feature helpful, right?”

- Seeking confirmation: “So you like the new design?”

- Interview dynamic: Participants want to be “good respondents” and avoid conflict

Better approaches:

- “Tell me about your experience with that feature.”

- “What’s your reaction to this design?”

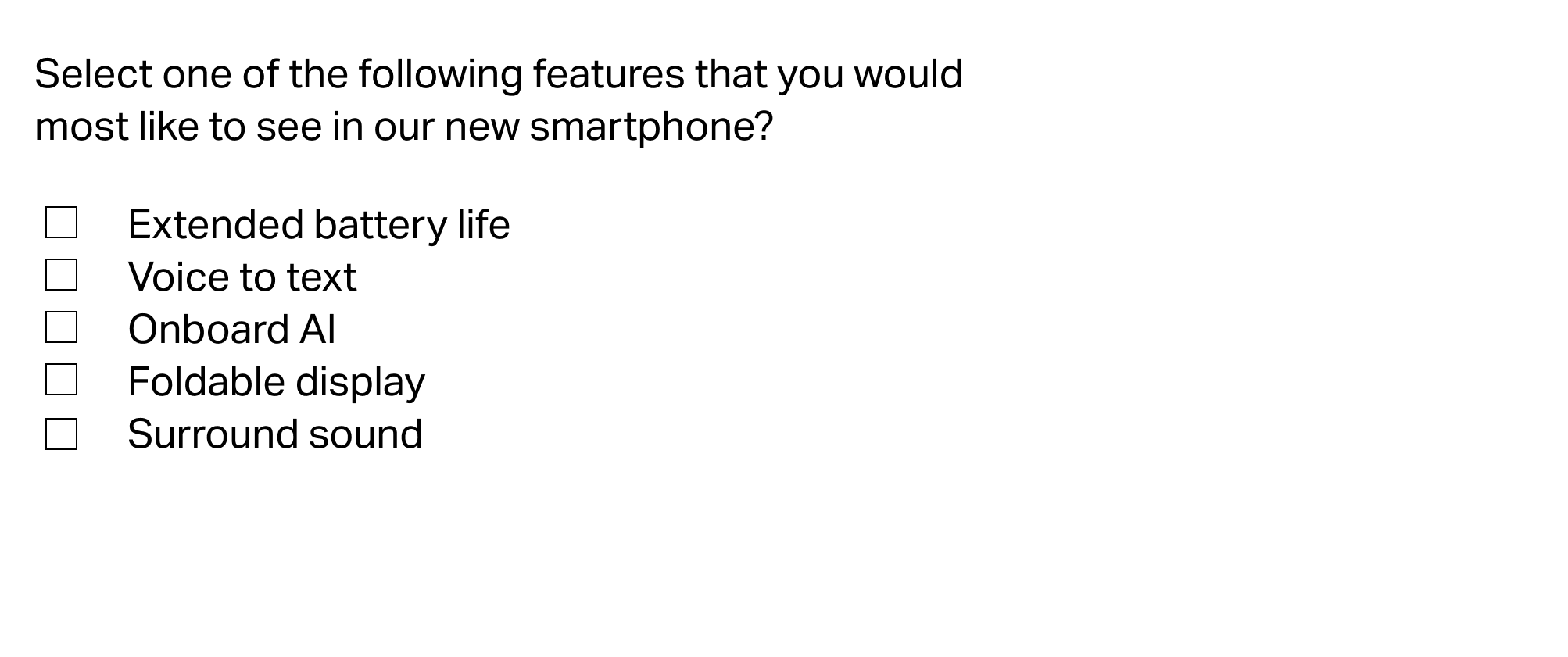

Question Design Issues

Evaluate this question:

Primacy and recency effects

Mitigating

General rules of thumb:

- First and last items in any list get disproportionate attention

- Middle items are most likely to be overlooked or forgotten

- Effect is stronger when participants are rushed or cognitively overloaded

- Written lists show stronger primacy effects; spoken lists show stronger recency effects

In qualitative research:

- Rotate order of concepts, stimuli, or topics across interviews

- Don’t always start with your “favorite” concept or most important question

- Be aware that early themes discussed may influence how participants frame later topics

- Consider breaking up long lists of probes or topics with natural conversation

- Save your most important questions for the middle of the session when rapport is built but fatigue hasn’t set in

Beware your framing!

How likely are you to purchase our new yogurt, which is 95% fat-free?

vs.

How likely are you to purchase our new yogurt, which contains only 5% milk fat?

Study Design Issues

Passionate about gourmet coffee? Take our survey for a chance to win a year’s supply!

Passionate about gourmet coffee? Take our survey for a chance to win a year’s supply!

Self-Selection Bias

Non-response bias

Non-Response bias

The impact from the lack of response by significant groups in your sample who have material representation in the population of your study.

Present in almost every study.

Affect heuristic

Key Takeaways

For your fieldwork:

- Awareness of these patterns helps you design better questions and probe more effectively

- Most biases aren’t “bad.” They’re natural shortcuts that become problems when unrecognized

- Your job as a researcher is to create conditions where participants can give you their authentic perspective

Remember:

- Start with open-ended questions before introducing concepts or stimuli

- Rotate order of topics and materials across interviews

- Probe beyond first responses; ask “why” and “tell me more”

- Pay attention to your own confirmation bias during analysis

Bottom line: Good qualitative research is about understanding and working with psychology and natural human tendencies.

Social Pressure Biases